"I cannot know whether the infinite forest has begun in me the process that has led so many others to utter, irremediable madness. If this is the case, all I can do is ask for forgiveness and understanding, as the display I witnessed during those enchanted hours was such that I find it impossible to describe in a language that would make others understand its beauty and splendour; I only know that when I returned, I had turned into another man."

— Embrace of the Serpent (2015), Ciro Guerra

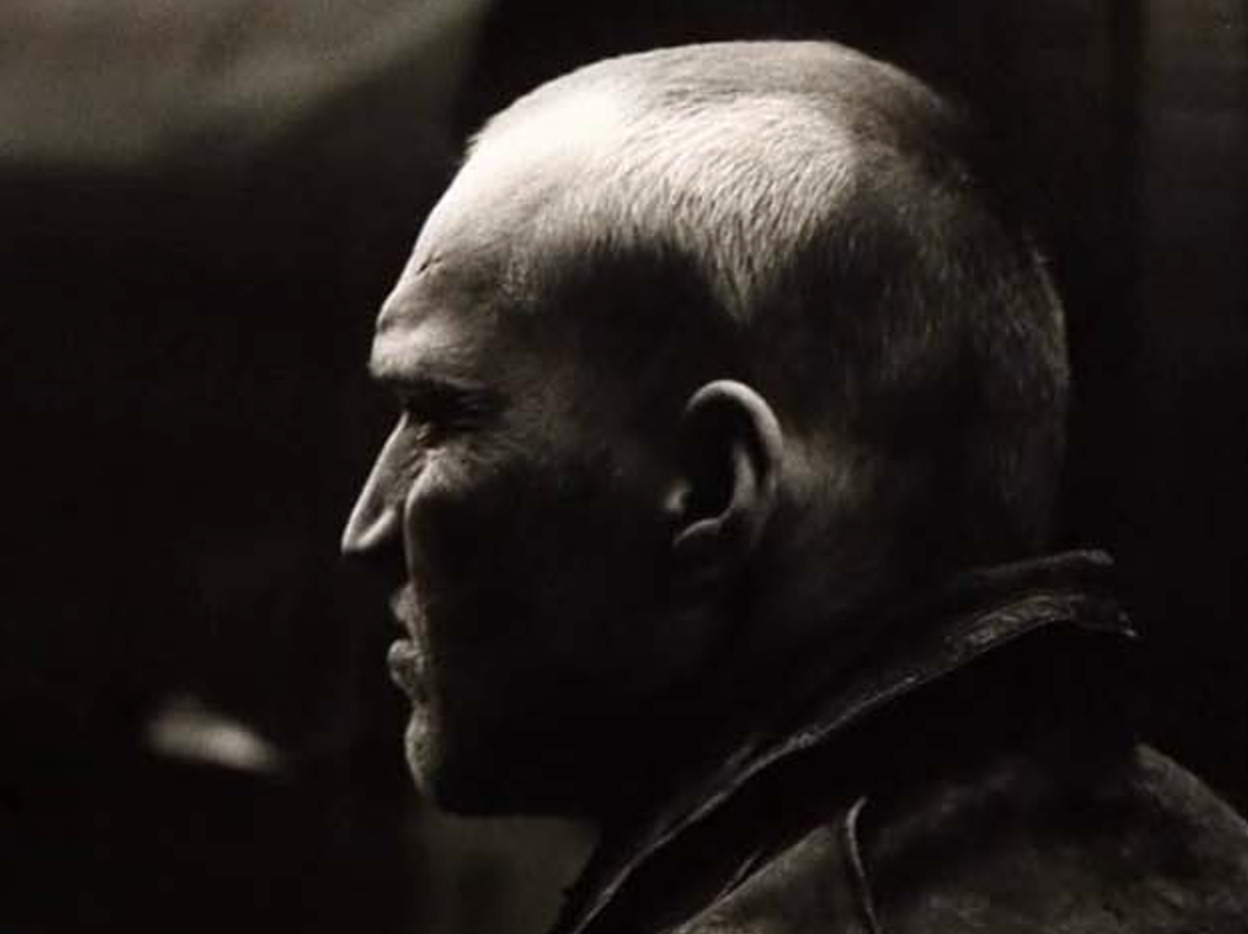

With stunning monochrome 35mm cinematography, piercingly profound dialogue, and an intensely atmospheric score, Embrace of the Serpent's masterfully concocted cinematic experience unfolds like a potent psychedelic elixir from which one awakens a new and transfigured consciousness.

It is a rare and precious event indeed when one happens upon such a formidable and intoxicating piece of art—a film, a novel, a musical composition—that it has the power, with great beauty and poignancy, to deeply disturb one’s most entrenched notions about our individual and collective existence.

Colombian director Ciro Guerra's Embrace of the Serpent is such a masterwork, uncovering at once among the darkest forms of human cruelty, madness, and suffering, as well as our indomitable resilience and ineffable beauty.

Within the confines of an Amazonian river, Guerra paints a fiercely telling autobiographical picture of our species and of our very souls; one woven through the many layers and dynamic interplay of physical and immaterial dimensions, rendering its evocations cosmic beyond all words and linear comprehension.

Employing hauntingly evocative imagery and thought-provoking cinematic discourses, the serpentine film progressively writhes itself through the backdoor and into the deep-seated privacy of our minds, and thereupon sits with us in stark confrontation with some of the most piercing questions we are to ask ourselves moving forward: that of our origins and destinies, our fundamental notions of self and other, and our dire responsibility to the evolution of man and earth in an age of unspeakable spiritual and ecological crisis.

Loosely based on the real-life diaries of two Western scientists, Embrace of the Serpent intertwines the journeys through the Amazon of a German ethnographer, and, 30 years later, of an American botanist following in his footsteps, as each is guided by Karamakate, an Amazonian shaman and sole survivor of his tribe. Though each expedition is defined on the surface level by a search for the Yakruna, a sacred and medicinal hallucinogenic plant, the dramas that punctuate each journey—spanning suspicion, comeraderie, betrayal, loneliness, and enlightenment—reveal far-reaching insights into the deeper historical, political, and spiritual human condition at large.

As a film, Embrace of the Serpent is no mere entertainment. Contextualised in our era of humanity in which untold suffering has continuously been unfolding, and in which the extremes of human unconsciousness are most disturbingly manifest, the work of art establishes itself as a rude, yet hopeful, profound, and most exhilarating awakening. Its present-day apparition is a sincere intimation of human enlightenment, and with it the concomitant plea for humanity to take a hard look at itself, and through itself, lest we descend into irrevocable disconnection and hysteria. It is a call for the return to the ancient wisdom and beauty found in our primordial connection with each other, with the animals, forests, and rivers, and with our deepest selves in the core of our consciousness—the same indigenous connection which has been severed, debauched, and sociopolitically stigmatised in direct conjunction with the purported ascent of civilisation since the dawn of history.

Set in an era reeling from 340 years of Spain's violent colonial rule imposed upon Native American populations, the film impels us to bear witness to some of the most alarmingly disturbing reverberations of colonialism on indigenous and ecological dignity in human history, all while employing scathing imagery that linger to haunt the imagination long after they are shown. Not only do they reveal the gruesomeness of colonial rule and its numerous accompanying human rights abuses, they show us, above all, the darkness which cuts through the heart of every man and woman, that rears its lethal head in the deep fissures of disconnect between each individual and his surroundings that pervade the modern world. Far from delivering a partisan thesis, however, the film is careful in conveying the message that whichever "side" one may fall on, we all reveal ourselves as suffering victims of humanity's most tragic narratives of prejudice and disconnection.

Embrace of the Serpent is not a film that will reach everybody. And yet it is imperative that it does. To receptive viewers, an exploration into the spiritual and ontological core of man is paved. It is a journey down the morbid truths, awe-inspiring beauty, and venerable wisdom that make up the rawness of our reality; the truths which we must fully grasp and consciously confront in order to collectively manifest a better world than the burning building in which we have found ourselves awakening to when we were born.

Indeed, though difficult to stomach, let alone digest into a contextualised cognisance of the extents of the horrors of which humanity is capable, the few morbid images and allusions shown, we come to understand, have a need to be seen, to be grasped, to be swallowed into the pits of our stomachs. And yet, put here in stark contrast with the pain of being human are some of the grandest beauties of which we are capable, whether in our own embodiment or in our deepest sensitivities. From our kinship and courage to our poetry and dreams, from the heights of human art and culture to the sights and sounds of nature pristine, the subtle touch of beauty as a virtue is veritably not forgotten of in the little parentheses of quiet and melancholic reflection embedded within the film.

[picture of night sky]

This juxtaposition of the greatest beauties and ugliest manifestations of earthen existence gives one such a feeling that becomes rather ineffable, indescribable; perhaps almost too much bear and to comprehend, compelling in us, without words, a kind of surreal and amorphous philosophical reverie that heavily tugs at the heart, without answer, without end. In this way, each heart-rending sequence, contrastive dialectic, and beatific vision shown progressively evokes a wholeheartedly expansive state of consciousness and cosmic perspective that is otherwise often only afforded us in the glimpses of truth that emerge either through deep meditative states or through the ingestion of substances that are capable of freeing the spirit from the historically- and intellectually-bound shackles of the mind.

Indeed, Embrace of the Serpent is, in the most dignified possible meaning of the label, a truly psychedelic film.

Into the Nature of Reality: Reigniting the Dawn

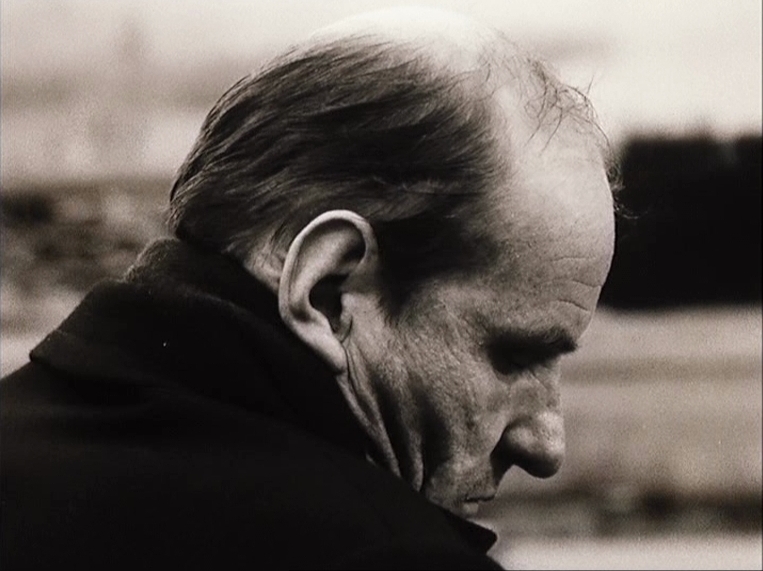

True to psychedelic fashion, Guerra is not shy in asking of us to leave our familiar conventions of morality, beauty, and the nature of existence at the door. In a conceptual rejection of the concrete monopoly of time and linearity, parallel back-and-forths between poignantly connected timelines and ideas communicate a timelessness and shared humanity that compellingly pierces the viewer's soul to reach a truth long buried within us from birth, and which we have long since been conditioned to forget. The only truth that transcends time and space is that of who we really are, deep down: the selflessness of pure awareness and the interconnectedness of all life that is to dawn most viscerally on the Shaman who, according to Karamakate, is to "abandon all and go alone to the jungle, guided only by [his] dreams ... In this journey, he has to find out, in solitude and silence, who he really is." As such the core question of man remains ever obstinate and absolute: the eerily familiar question of "Who am I?" reverberates on from the infinite abyss, the dark wild jungles of our past, ever echoing in neglected whispers into the light and marrow of our present consciousness, generation after generation of lost, unconscious, and ultimately despairing civilisations.

Like that of the shaman, the White wanderers' journey through the Amazonian landscape is made poignant and substantive only by their solitary expedition into the inscape of their own spirit. Through looking inward rather than outside oneself, and by way of an intimate connection to the source of being, the knowledge and wisdom of the galaxies—as well as the very truth of Self—unfurl like a golden carnation, revealing themselves in transfigured states of consciousness, visions and dreams awake, as they would appear to have for eons to earth's ancient civilisations who have the ear to listen, the heart to dream, the song to sing. It is this ancient spirit song which Karamakate toils to uphold and protect from the White Man's destructive touch—and which he, alas, had felt himself to lose, a process by which he transmutes into a chullachaqui, an empty and hollow copy of a person that drifts like a ghost, having lost his connection to the earthsong, the cosmic origin of life.

In a modern global discourse whose truths can only be validated by the paradigms and first principles of rational reductivism, we are challenged here, thus, to re-examine the respectively antithetical first principles which we have so far reduced to the status of mythological fantasy and primitive ignorance. Whether manifest in Shamanic self-transfiguration, the erection of monumental structures, or inexplicable knowledge with regards to everything from astronomy to medicine, the allusions to an unfathomable well of wisdom to which ancient peoples were connected cannot be superficially dismissed. The instruments of science and mathematical precision which have afforded us untold technological powers (the exhaustive ethical matters and ontological claims of which are more inherently dubious and ill-defined than are recognised to be in the Western psycho-spiritual canon) are but few of the many instruments of exploration within our reach. From the solitary retreat of the Shaman to his naturalistic medicines, to modern synthesised substances and esoteric meditations, to the voices of schizophrenia and the revelations of dreams and inner journeys, a plethora of alternative tools of the inner realms are offered us in abundance across all regions of the world and all levels of consciousness.

In an era where the absolute authority of our reductivist-materialist philosophy, addictive worship of post-industrial technology, and widespread social rejection of spiritual endeavours have proven themselves inadequate in dealing with—and are even perhaps accountable for—the convergence of spiritual, ecological, and humanitarian crises we now face, we must hereby ready ourselves in accepting our responsibility for the receptivity necessary to decondition and release ourselves from contemporary dogmatic paradigms, so that we may, perhaps and with due time, come to see the reality of existence as it purely is, as if through clear glass for the first time, as if through the eyes of a newborn baby: unconditioned, untethered and unbounded.

Inquiries into the nature of reality reveal themselves in the film both with cunning subtlety and dazzling resplendence. The recurring motif of primitive, visionary forms and symbols, for instance, punctuate the film from beginning to end. With sequences particularly reminiscent of Plato's fiery cave and his world of ideas, an academic and philosophical bridge to the White Man's world is tacitly drawn, further underpinning the timelessness and spacelessness of the essence of life and philosophy, of the the spirituality of all humankind. The dream world inhabited by Plato's forms, to which our protagonists retreat whether in their sleep or in their visionary glimpses into the mystical dimension, is seen to spill out into reality in the form of drawings and symbols. This is in much the same way, one may discern, as that by which the world of imagination materialises into our reality: indeed, what we may perceive to be the dead and impersonal Newtonian-Cartesian-Darwinian physical universe may itself be but the shadows cast by the imaginary forms and ideas manifested in the light of the germinal consciousness from which we are inseparable. If so, are we as much prisoners to the forms as were Sciamanna's children around the fire, whose entire senses of their reality were moulded and dictated by their self-appointed Godhead and idol? What validity, then, hold the laws which we had come to believe make up an absolute and overruling universe?

If the so-called physical world is but a manifestation of the infinite imagination of being, it is surely only a provisional arrangement within our current fabric of space-time materiality—yet one bearing the utmostly felt reality of our highest pains and ecstasies. The story of our existence thus becomes just that: a vivid and legendary fable; self-contained, self-created, yet ever changeable; its fate shaped only by the collective power of our minds, the drive of our hearts, the steersman of our souls. We have locked ourselves away from infinity. By connecting with our inner selves, then, ineffable powers of the imagination to shape our destinies begin to unfurl. Without the weight of our symbols, judgments, and appointed conceptual and spiritual authorities, what free existences might await us at the edge of the known universe?

Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing,

there is a field. I'll meet you there.

When the soul lies down in that grass,

the world is too full to talk about.

Ideas, language, even the phrase "each other" doesn't make any sense.

Mevlana Jelaluddin Rumi - 13th century Persian Sunni Muslim poet, jurist, Islamic scholar, theologian, and Sufi mystic

Back to the Great Unknown

Released in 2015, Embrace of the Serpent is a reflection of its time that only becomes ever more critically pertinent as the crises of history are converging into a breaking point. As we are progressively revealed with utmost gravity and intensity the planet-wide depravity of an existential degree that we can no longer ignore, the confronting reality of our current mode of existence becomes a desperate plea for the cessation of the spiritual madness for which we are all individually responsible. Our familiar modern world of manufactured industrial realities, closed doors and lonesome fears, as many of us realise, has been unabatingly built on the backs of colonised peoples since the dawn of Western imperialism. Perhaps, we intuit, the misery of the Western man is but a droplet's reflection of the sea of suffering that birthed it... a sea shielded from sight, buried under a manufactured historical narrative concretised to make us forget our natural beauty, our earthly origin, our ancient song.

Yet, despite its unforgiving diagnoses, the film - with nine different spoken languages - exquisitely retains a just and thought-provoking balance between The White Man and the Amazonian natives, between the profound beauties as well as the evils of modern civilisation, and even between the childlike innocence and the spiritual gravity of humankind, whether Brown or White, in monochrome or technicolour. The film thus delicately yet effectively instils in us a sense of freedom and receptiveness of the psyche necessary to hold conflicting ideas, cultures, and unanswerable questions in a mind over-habituated to its own limited umwelt and its crystalised conditioning under rationalism and scientific reductivism, and that are therefore indispensable to the expansion of our evolution and understanding of one another, of nature, and of our true selves.

In a modern Western culture in which we all too often shy away from sincere spiritual dialogue due to the reigning psychological influences of the dogmatic monotheisms of Christianity, Secular Atheism, and of a rigid reticence of the soul ostensibly veiled in the name of Propriety and Political Correctness, we must let ourselves collectively come squarely back to what Terence McKenna eloquently calls the great Who Knows?, Charles Eisenstein's Space Between Stories in which the mind is free from all conceptual conditioning, a space in which we are irrefutably and unmitigatedly free to question and free to wonder with the very same unyielding faith in the unknown that has propelled human intellectual inquiry since the scientific Enlightenment into this state of material prowess we so enjoy today.

"What psychedelics do, in terms of impact on the physical brain and organism of human beings, is they withdraw cultural programming. They dissolve cultural assumptions. They lift you out of that reassuring crystal and matrix of interlocking truths which are lies, and instead they throw you into the present of the great Who Knows? -- the mystery... the mystery that has been banished from Western thought since the rise of Christianity and the suppression of mystery religions [...] What is revealed through the psychedelic experience, I think, is a higher-dimensional perspective on reality."

By inhabiting that empty space of complete spiritual surrender and abandonment to faith, we arrive at a state of consciousness, of non-belief espoused by the great Oriental philosophies of Buddhism, Vedanta, and Taoism. As Alan Watts writes:

"The common error of ordinary religious practice is to mistake the symbol for the reality, to look at the finger pointing the way and then to suck it for comfort rather than follow it. Religious ideas are like words--of little use, and often misleading, unless you know the concrete realities to which they refer. The word "water" is a useful means of communication amongst those who know water. The same is true of the word and the idea called 'God.'

"The reality which corresponds to 'God' and 'eternal life' is honest, above-board, plain, and open for all to see. But the seeing requires a correction of mind, just as clear vision sometimes requires a correction of the eyes. [...] To 'have' running water you must let go of it and let it run. The same is true of life and of God. The present phase of human thought and history is especially ripe for this 'letting go.' Our minds have been prepared for it by this very collapse of the beliefs in which we have sought security. [...] This disappearance of the old rocks and absolutes is no calamity, but rather a blessing. It almost compels us to face reality with open minds, and you can only know God through an open mind just as you can only see the sky through a clear window. You will not see the sky if you have covered the glass with blue paint.

"We find life meaningful only when we have seen that it is without purpose, and know the 'mystery of the universe' only when we are convinced that we know nothing about it at all. The ordinary agnostic, relativist, or materialist fails to reach this point because he does not follow his line of thought consistently to its end. All too soon he abandons faith, openness to reality, and lets his mind harden into doctrine. The discovery of the mystery, the wonder beyond all wonders, needs no belief, for we can only believe in what we have already known, preconceived, and imagined. But this is beyond any imagination. We have but to open the eyes of the mind wide enough, and 'the truth will out.'"

As Embrace of the Serpent offers us a revealing glimpse into the lives of communities devastated by religious madness as the inevitable upshot of unbridled ideology, as well as the contrastive serenity of Karamakate's naturalistic spiritualism (itself not without its own vanities, one may infer),

Under close inspection, it becomes evident that our technological apparatuses must fail by their very ontology to pin down our formless consciousness, our awareness, our "being here and not there," the ghost in the machine for which perceived and measurable physical phenomena can only, at very best, stand as dead and impersonal simulacra, like Plato's proverbial shadows cast upon the grotto canvas. It may be due time for the exhaustive and life-consuming programme of management and control of our technological efforts to surrender its suffocating grasp in the attempt of defining all reality, and with it all our ethereal human feelings and philosophical wanderings, so we can finally admit and thereby surrender to the mystery of our own Being. Thus relieved of the weight of our left-brained hubris, we may one day open our minds up to the spiritual dimension of nature—not through words or data but through the kernel reality of our felt experiences—for Her to be palpably heard, felt, and, perhaps, even understood.

On Nature's Spiritual Dimension

Embrace of the Serpent's serpentine epic hearkens back to our yesteryears of mythology and storytelling over the fire, the germinal gleam of culture and community, the cradle of our very humanity. Speaking viscerally to the sparks of the imagination elicited within the receptive listener, within the open and fertile consciousness of the child in each of us, the film takes us back to a world of animistic mountains and totemic animals, divining Shamans and the spirits of dreams; of sincerely bearing within our hearts and those of our communities an intimate and reverent relationship with the Great Other, a spirit world beyond our grasp, the movers of suns and the pulsation of all life. Perhaps it is time for the hubris of our current, implicit meta-narratives about existence to give way to a humility that allows for other intelligences to share our space, in whatever form they may be: whether as a Jungian, underlying current of collective creative wisdom that runs beneath all minds, inter-dimensional entities, perhaps (why not?), a Mother Earth or Gaia, ... such a concept would not seem so incredulous were we to return to the enviable sense of wonder of our forebears that left our minds open to all the possibilities that our ultimately such mysterious universe may have to offer. Whatever tangible or intangible truths this may imply, this presence of a Great Other has already been palpably felt and acknowledged—communicated with, even—by countless of history's explorers of mind and reality. The quest of modern Western civilisation to now uncover the truths or untruths behind these ancient claims may well reveal them to be more than mere fantasies of the mind; and if so, we may open doors for humanity on an enormously existential level that might just change everything. In any case, it would stand to reason that the quest is worth taking seriously, in a world, no less, of tired nihilism and voids where wonder, magic and adventure once defined the landscapes of our existences.

Terence McKenna once said, “the artist’s task is to save the soul of mankind; and anything less is a dithering while Rome burns. Because of the artists, who are self-selected, for being able to journey into the Other, if the artists cannot find the way, then the way cannot be found.” Embrace of the Serpent is at once a chronicle of such a journey, and at once the subsequent call-to-awakening of the shamanic explorer as he stumbles back into a burning civilisation for which the spark of hope for redemption seems all but lost.